Linguistics 522

Lecture 3

Phrase-markers

Structure-dependence is the theme of our course.

We have been arguing for it in terms of the trees

we draw for sentences, which capture

information of two kinds:

- Syntactic categories

- Syntactic structure (phrases)

First phrasehood.

The boy must seem incredibly stupid to that girl.

- [The boy] must [seem [incredibly stupid] [ to [that girl]]].

Second, categoriality.

The trees we'll be using then embody two notions,

constituency (phrasehood) and categoriality.

Radford doesn't call these structures trees.

He calls them phrase-markers. The term

tree is actually more

popular among linguists and computer scientists

alike. But is isn't more popular

with one very important guy, Noam

Chomsky. For some reason

never made particularly clear to me,

Noam Chomsky never talks about trees.

He always talks about phrase markers.

Radford follows Chomsky here.

Defining basic Terms

graph, node, root node:

Whether you say tree or phrase-marker,

the structure can be formally thought of as a graph,

a mathematical term that's

particularly important in computer science.

A graph is just any structure with points

and lines between them, and a tree

is just a special kind of graph with a fussier definition.

The points in a graph are also called

nodes and that is the term linguists use

for the points in a phrase markers or a

tree. Some of the nodes in

tree (1) on p. 110 are the S-node (called

the root node, because it's the top),

the VP node, the NP node and the P node.

immediately dominates, dominates, exhaustively dominates, mother,

daughter, sister, precedes, immediately precedes

|

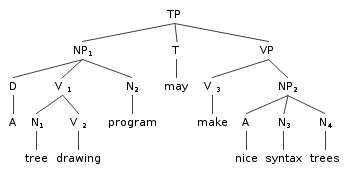

(1)

|

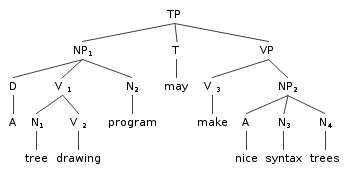

immediately dominates: In tree (1) on the left, TP immediately

dominates NP1, T, and VP. NP immediate dominates D, V1

and N. VP immediately

dominates V3 and NP2.

mother, daughter, sister: used to describe nodes in an immediate

dominance relation. A node M is the mother of a node D, if and

only if M immediately dominates D. In the same situation we say D is a

daughter of M. That is, a node D is the daughter of a

node M if and only if M immediately dominates D. Two nodes

that have the same mother are sisters. In tree

(1), NP1 is the mother of D, V1

and N2, and

D, V1

and N2 are the daughters of NP1.

NP1 is NOT the mother of

V2 because NP1 does not immediately

dominate V2. In fact,

NP1 is what you might call the grandmother

of V2 (the mother of its mother).

exhaustively dominates: A node M exhaustively

dominates a set of nodes D1 through Dn if and only if

M is the mother of each D' and there are no other nodes

M is the mother of. In other words, the set

of nodes a mother dominates must include all her daughters.

In tree tree (1) on the left, TP does not exhaustively dominate

NP and VP. It exhaustively dominates NP, T, and VP.

dominates: Dominates is defined as follows:

- A node A dominates a node B if A immediately dominates B

- A node A dominates a node B if there is a node C such

C dominates B and A dominates C.

So this brings inheritance in. A dominates B not just when

A is the mother of B, but also when it's the grandmother,

or the great-great grandmother, or the great-great-great grandmother,

and so on. In tree tree (1) on the left, TP dominates NP, T, and VP

(because it immediately dominates them), but it also dominates

D, N1, V1, V2, and V3

(among other nodes).

immediately precedes: A node A immediately precedes a node B if it

is immediately to the left of B. In tree (1) on the left,

NP1 immediately precedes

T and T immediately precedes VP, but NP1 does

not immediately precede VP.

T also immediately precedes V3 M in tree (1). And

T also immediately

precedes VP and it also immediately precedes V.

precedes:

Precedes is defined as follows:

- A node A precedes a node B if A immediately precedes B

- A node A precedes a node B if there is a node C such

C precedes B and A precedes C.

So NP1 precedes T because it immediately precedes T in tree (1),

but it also precedes VP, V3, and NP2.

Note that dominance and precedence are mutually exclusive.

A node X cannot both dominate and precede another node Y.

Essentially what this terminology does is break phrasehood

down into two parts, dominance and precedence. A phrase

is series of elements (words or phrases), dominated

by a single node, which come in a fixed order.

|

Constituent, constituent of, immediate constituent of:

A set of nodes form a constituent of some sentence structure

if and only if they are exhaustively

dominated by a single node in that structure.

A node A is a constituent of of some

other node B if and only if B dominates A.

A node A is an immediate constituent of of some

other node B if and only if B immediately dominates A.

The following table summarizes these points:

|

A

|

(immediately) dominates

|

C

|

|

|

iff

|

|

|

C

|

is a(n immediate) constituent of

|

A

|

|

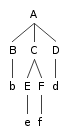

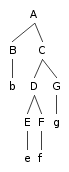

(2)

|

Observation

We now have four ways of expressing the relation

between nodes that is exemplified in tree (2):

- A immediately dominates C.

- A is the mother of C.

- C is a daughter of A.

- C is an immediate constituent of A.

These all mean the same thing.

Defining traditional grammatical terms, pp. 112, 113

Not important at this stage

C-Command

We've talked about mothers, grandmothers, great grandmothers,

and so on, which I'll write

great ... grand mothers. Now it's time to talk about nieces

and great ... nieces.

Branching node:

A node is branching if and only if there are at least

two nodes in the set of nodes it exhaustively dominates.

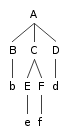

C-Command:

X C-commands Y if and only if the lowest branching

node dominating X also dominates Y and X does NOT dominate

Y nor does Y dominate X.

In (10) on p. 115,

Consider the following example:

|

(3)

|

B C-Commands C, D, E, F, and G.

C C-commands B [so C and B C-command each other.]

C does

NOT C-command D,E,F,G, because it dominates all of them.

|

Here is where the nieces and great ... nieces come in:

A node C-commands its sisters and its nieces and its

great .... nieces, that is the daughters and grandaughters

and great- .... granddaughters of its sisters. Note that sisters

C-command each other.

Anaphora and C-command

Reflexives and reciprocals are special forms that occur only in

special syntactic contexts:

- John shaves himself often.

- John and Mary like each other.

The claim made in the text is reflexives and reciprocals are dependent

in a special way. Like pronouns they require antecedents. Unlike

pronouns they require

those antecedents to be in a special syntactic configuration:

- Mary liked him.

- * Mary liked himself.

- John's mother likes him.

- * John's mother likes himself.

- His mother likes John.

- * Himself's mother likes John.

- * Himself likes John.

Parallel facts for each other.

- Mary and Sue liked each other.

- * Mary and Sue's mother likes each other.

- * Each other likes Mary and Sue.

Words like reflexives and reciprocals that have this special

dependency property are called anaphors.

The following proposal is made for anaphors:

Principle A

- C-Command condition on anaphors.

-

- An anaphor must have an antecedent that both precedes

and C-commands it.

This accounts for all the ungrammatical examples above. For example:

There is no semantically acceptable antecedent that both precedes

and C-commands himself.

- * John's mother likes himself.

Here there is a semantically acceptable antecedent that

precedes himself but it does not C-command

himself. The first branching node above

John does not dominate himself.

This example shows that precedence alone is not enough

to predict the distribution of anaphors.

The following example shows that C-command alone is not anough:

- * We gave pictures of each other to John and Mary.

The account also accounts for the ambiguity of examples like this

- We shot arrows at each other.

It could be that each arrow shooter is shooting at the

other. Or it could be that they are shooting each arrow at the other's

arrow. In other words, the antecedent of the reciprocal could

be We or it could be arrows. Both NPs C-command

and precede the reciprocal. Therefore both are candidate antecedents by

our principle.

Questions to Think About

Now think about the following example:

- Sarah and Sue talked to Mark and Hubert about each other.

Is there an analogous ambiguity? More importantly,

is there a problem for Principle A? Think about the tree for this example.

Now think about this one:

- Mary and Sue thought those pictures of each other were great.

- Mary and Sue's pictures of each other were flattering.

Same question.

And finally:

- Those pictures of themselves pleased Mary and Sue.

Same question.

Phrase-Structure rules and lexicon

We now move to a more precise statement of what the

grammar looks like.

We need a finite set of rules that can "generate"

an infinite set of sentences.

We're going to have two kinds of "rules"

- Phrase-structure rules, which are used

to "admit" or "license" phrase-marers (trees)

and look like this:

- Lexical entries, which for the moment, just

assign categories to words. They look like this:

Phrase-structure rules state immediate dominance

and precedence relations. The phrase-structure

rule for TP says a TP can immediately dominate a VP preceded

by an T preceded by an NP.

The lexical entry for "boy"

says "boy" is a noun.

We'll call the categories that belong to

some lexical entry lexical

categories.

We call the nodes in a tree that dominate

words or nothing terminal nodes.

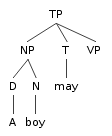

Consider the following partial tree:

The nodes D,N,T, and VP are all terminal nodes

in this tree.

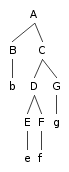

Phrase structure-rules and phrase markers

A phrase-structure rule admits local trees:

admits

A tree is well-formed with respect to a grammar G if and only if

it meets two conditions:

- All the local trees are admitted by phrase-structure

rules in G.

- All the terminal nodes dominate words of the appropriate

lexical category as defined by the lexicon of G.

Definition of grammaticality

We call the words admitted by some well-formed

tree the yield of that tree.

Now we can say what strings are generated by a grammar G.

A string is grammatical if and only if

it it is the yield of some tree admitted by

the grammar.

Determining when a sentence is grammatical

accoding to a grammar

Our job in this course is not so much to find the right

grammar of English as to find ways of

evaluating candiadtre grammars. As a result,

the most important skill you learn in this course

will be determining whether or not some proposed

grammar characterizes an example sentence

as grammatical.

If the grammar says the sentence is grammatical

and our intuitions tell us it's grammatical,

good for the grammar.

If the grammar says the the sentence is

grammatical and our intuitions

tell us it's ungrammatical, we

say the grammar overgenerates.

If the grammar says the the sentence is

ungrammatical and our intuitions

tell us it's grammatical, we

say the grammar undergenerates.

It's pretty safe to safe all the grammars we consider

in this course will do both. It will undergenerate

because there are lots of constructions we won't consider.

For example:

John grew happier, the more he ate.

The italicized constituent begins with a determiner,

like a noun phrase, but lacks a head noun. None

of the rules we consider in this course will generate

this sort of thing.

Our rules will overgenerate because even for the constructions

we DO consider there are all kinds of constraints we are

ignoring. For example:

(= 26, PS rule 6), p. 134, generates NPs like

But it also allows

So determiners and nouns have number,

and they must agree, and we haven't yet found a way to account for this.

The skill we need for this course is to be able to take a set of rules

and a set of data and decide whether the rules account

for the data. If not, we need to be able to decide on

the simplest change to our rules that will extend

them to cover the data.

Execrcise V, p. 160 is about this.

Particles and conjunctions

The question raised is whether we need to recognize new lexical

categories for particles and conjunctions.

Particles first:

- He put on his hat.

- If you pull too hard, the handle will come off.

- He was leaning too far out over the side and fell out.

- He went up to see the manager.

What syntactic category that

we already recognize seems

like closest fit for these particles?

Some argue they should be assimilated to

prepositions, partly because they can (often)

be replaced with PPs.

- He put his hat on his head.

- If you pull too hard, the handle will come off the door.

- He was leaning too far out over the side and fell out the window.

- He went up the stairs to see the manager.

Radford notes prepositions can also function

as subordinating conjunctions:

- After he ate he fell asleep.

- After the meal, he fell asleep.

- Matilda was envied for being such a good syntactician.

- Matilda was envied for her talent.

- I should wait until you return.

- I should wait until your return.

- There has been no trouble since you left.

- There has been no trouble since your departure.

And sometimes a single word can be a preposition, a particle, and a conjunction:

- There has been no trouble since.

- There has been no trouble since your departure.

- There has been no trouble since you left.

See also examples with after, before, p. 134.

So what Radford argues for (Emonds's analysis) is that there are

three uses of prepositions, the canonical preposition

use (where they take an NP complement), the conjunction

use (they take a clause complement) and the particle use (they

take no complement). This is just the kind of variation

we see with verbs.

- John knows.

- John knows the answer.

- John knows that Columbus landed in the West Indies.

Some prepositions take only the transitive and transitive

option and not sentential complements:

- John went out.

- John went out the door.

- * John went out Mary exited.

Again there are verbs that show THIS pattern:

- John ate.

- John ate the apple.

- * John ate Mary ate.

Another argument, essentially a distributional

argument, is that prepopositions, conjunctions,

and particles may all take the same modifiers:

- John left immediately before the party started.

- John left immediately before that.

- John left immediately before.

Now what about restrictions on all this behavior?

Many prepositions cannot be used as particles:

- * He left until.

- * He left during.

Many conjunctions (what Emonds would call

prepositions that take S complements) do not take NP complements:

But Emonds's story is going to be that these restrictions

are not categorial. They are lexical restrictions.

That is, these differences among what Emonds call prepositions

are like the differenvces between ordinary verbs.

Some verbs take S- but not NP-complements:

- John hopes Mary will arrive soon.

- * John hopes Mary's arrival.

Some take NPs but not Ss:

- * John enjoyed that Mary danced.

- John enjoyed Mary's dance.

Some take no complement at all:

- John fell.

- * John fell the stairs.

So on the old analysis, Prepositions only

took NP complements; they were

a defective category.

The new analysis makes Prepositions look much more like

other categories.

Notice all the argumentation is about parsimony here.

Let's have fewer lexical categoires, because

overall that gives us a simpler picture of grammar.

Why is simpler better? Well if we constrain

the class of grammars (by constraining the class of

categories they can use), then maybe we are

on the way to explaining why children

learn them so easily.

We'll see.

Conflating categories

Continuing along the same lines. Now we try to constrain

the class of categories by collapsing several categories together.

First we try to collapse adjectives and adverbs.

Arguments:

- Morphological: Both adjectives and adverbs have comparative

and superlative forms

- Objection: Many adverbs form their comparative and

superlative forms not with -er and -est but with more

and most.

- Response: So do many adjectives like expensive

and probable.

- Often the same comparative form will be shared by

an adjective and its -ly counterpoart.

- She was happier than he was.

- * She works happilier than he does.

- She works happier than he does.

- Syntactic: Adjectives and Adverbs have similar premodifiers

like very, really, and extremely.

New official treatment: Adj and Adv get collapsed.

We call the new category A (rather than advective or adjerb).

Questions to Think about

Now think of an objection to collapsing adverbs

and adjectives. What's the first problem

that comes to mind?

Not conflating categories

The argument for conflating

Adj and Adv was really based on something

you may have learned about in previous

linguistics classes called

complementary distribution.

The idea is basically the Superman/ Clark Kent idea.

If there are two entities you

never see in the same place

at the same time, then maybe underlyingly

they're the same entity. It's just that

sometimes they're wearing glasses.

So the idea was that adverbs are just adjectives

wearing glasses.

In this particular case, the idea was that there's

one category which "surfaces" as an adjective

when it's modifying a Noun,

and as an Adverb everywhere else.

Compare this to the treatment of

allomorphy in the case of plural s

- fox: /f aa k s/ + /ax z/

- dog: /d ao g/ + /z/

- duck: /d uh k/ + /s/

Three different ways of pronouncing plural s.

These forms occur in complementary distribution.

That is, they not only occur in environments that

mutually exclude each other, but the environments

taken together, exhaust the possibilities.

Why not do more of the same?

Why not collapse adjectives and determiners?

There are a variety of facts that argue against

this.

The basic morphological argument is that there

is no shared morphology between determiners and adjectives:

- Adjectives have comparative and superlative forms; determiners do not

- Adjectives take -ly to become Adverbs; determiners do not

- Adjectives take -ness to become noun; determiners do not.

- And so on...

Distributional arguments:

- Different distributions. Determiner must always

precede adjective in an NP:

- The red book

- * Red the book

- Adjectives can iterate or "stack up" to the left of a

noun; determiners can not

- * a the book

- the big green machine

- More important (in my book). Adding a determiner

can an NP "complete". Adding an Adjective cannot:

- * book

- a book

- * favorite book

- my favorite book

- Determiners and Determiners can be conjoined;

adjectives and adjectives can be conjoined; determiners and

adjectives cannot.

- each and every way

- a lazy and inconsiderate man

- *each and lazy man

Semantic arguments.

- Selection between Adjectives and Nouns on semantic grounds

- Selection between

Sample exercise answers

Excercise VI. Example answers.

a: central determiner

- a few books: CENDET + POSTDET

- an additional book: CENDET + POSTDET

- half a book: PREDET + CENDET

- * a the book: * CENDET + CENDET

no: central determiner

no two books: CENDET + POSTDET

no additional book: CENDET + POSTDET

* no the book: * CENDET + CENDET

problem: *all no book: PREDET + CENDET