Linguistics 522

Lecture 2

Structure-dependence turns out to be a very important

notion.

We linked it to two ideas

- Syntactic categories

- Syntactic structure (phrases)

these correspond to the two things Carnie

talks about at the outset of Chapter two.

We take up phrasehood first.

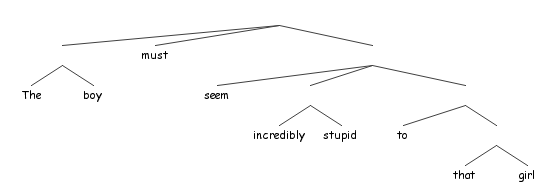

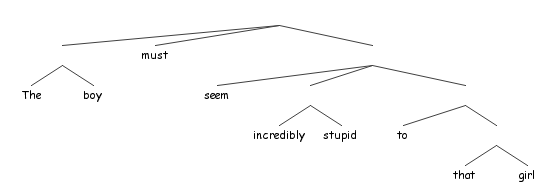

The boy must seem incredibly stupid to that girl.

[The boy] must [seem [incredibly stupid] [ to [that girl]]].

Everybody find this absolutely uncontroversial?

Sometimes in traditional grammar there's notion of a verb group.

The above proposal misses this completely. In

general there will be a number of plausible candidates

intuitions won't decide among. And as you

will see, linguists will disagree.

In general, we will need arguments

for phrasehood. Intuitions won't do.

So phrasehood is the first component of what Carnie means

by structure in structure dependence. The other component

is categoriality:

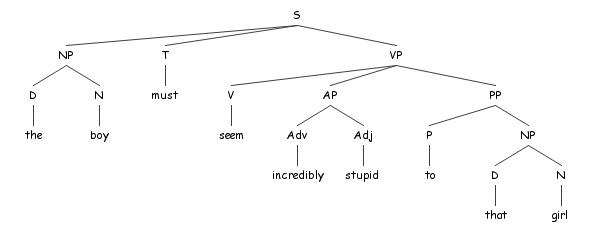

We have the same phrases as before exactly but

now they are labeled with labels like NP, M,

VP, AP, PP. As an alternative and completely

equivalent representation of the tree we have the labeled

bracketing in (5)

[S [NP [D the] [N boy] ] [T must ] [VP [V seem ][AP [Adv incredibly ] [Adj stupid ] ] [PP [P to ] [NP [D that ] [N girl ] ] ] ]]

In fact this is exactly the labeled bracketing that was used to generate the above

tree in the tree-drawing

web-site.

The trees we'll be using then embody two notions,

constituency (phrasehood) and categoriality.

There's a third notion which isn't really made explicit

in Chapter 2 but which will become important later.

Headedness. Each of the phrases has a word that it

is its head. We'll argue for this in detail

later but it's the head of the phrase that determines

many of its properties. For instance,

The man with two Cadillacs has man as its

head.

Here is some evidence:

- The man with two Cadillacs is over there. [singular agreement with man OK]

- * The man with two Cadillacs are over there. [singular agreement with Cadillacs not OK]

- * The men with a Cadillac is over there. [singular agreement with Cadillac not OK]

- The men with a Cadillac are over there. [plural agreement with men OK]

For NPs, the head determines its number agreement properties

and what kind of entity the NP as a whole

describes. The man with two Cadillacs

has man as its head

and refers to a man, not a Cadillac.

So we move on to arguments for kind of structure we're assuming.

Determining Parts of Speech

- Noun: table, destruction, family, theory ...

- Adjective: green, utter, delicious, syntactic

- Adverb: cleverly, very, quite

- Verb: walk, sleep, criticize...

- Modal: may, could, can, will...

- Preposition: of, about, on, on top of, with, to ...

- Determiner: the, every, few, many, more, seven, both, only,

my?...

Word-level Evidence

Word-level phonological evidence for lexical categories:

Phonology is sensitive to category[p. 56, (8)-(10)]

This argument needs to be adjusted slightly

for American speakers.

Semantics is sensitive to category.

Ambiguity of phrases:

- mistrust sores

- Be suspicious of wounds.

Notice headededness is changing as well as category.

Morphology is sensitive to category. Verb inflection

These inflections go on verbs, not adjectives,

not nouns. Criticisms?

Modals do inflect for tense:

- can, could

- shall, should

- may, might

Modals don't inflect completely like verbs.

Some modals lack past tense forms:

What do we SAY here when we mean the past tense form

of must?

Modals never have an ing form or participle form, never have an

agreeing form inflected in -s.

Adjectives and adverbs take -er. (16),(17), p. 59.

Nouns take plural -s.

Prepositions take NO inflection. [some languages

DO have inflecting prepositions.]

Determiners have no single defining morphological

characteristic. Hmmm. Worry about this.

Why no consistent inflection? Do any determiners take any inflection at

all? Well maybe.

What about my, his, her? Maybe these are possessive forms?

If so, they would be possessive forms of I, he, she.

But these are not determiners, so they're not what we're looking for now,

morphological processes that apply to determiners. And

in the end, we're not even going to be sure that

this process produces determiners, because

we're going to have some questions about whether possessives should be

thought of as determiners.

Here's an example to think about.

More is sometimes treated as the

comparative of many. This is too complicated to

argue for now, but the intuition is on the

basis of analogous pairs like these:

- John bought an cheap book.

- John bought a cheaper book (than Mary).

- The lecture attracted many students.

- The lecture attracted more students (than teachers).

In any case this lack of morphology for determiners seems

to be a peculiarity of English. In many

languages, detrminers inflect quite freely for

number and gender. Spanish, for example. Examples?

All of this was INFLECTIONAL morphology. There is

another kind of morphology called DERIVATIONAL.

Digression:

What is the difference between derivational and inflectional

morphology? Some diagnostics for inflectional affixes

- Attach outside of derivational affixes

try + -al => trial

try + -al + -s => trials

try + -s + -al => * triesal

- Productive over the entire category; doesn't change category

- Limited set of abstract semantic concepts: tense,

number, mood, comparative...

- Meaning change compositional and predictable. This is why

the dictionary conventions tend to

include all inflectional forms within the same

dictionary entry. Inflectional forms can be thought of

as being different form of same word. We can't always trust dictionary

entries because they include a lot of Miss Grundy

grammar (prescriptive grammar), but in this case they

seem to correspond to a deep linguistic fact.

We can also find derivational morphological evidence.

-ly example from text

adj + ly => adv

-ness example from lecture 1

adj + ness => noun

Summarizing the evidence thus far:

We've argued for lexical categories on the basis

of phonological, semantic, and morphological evidence.

The morphological evidence was of two kinds, derivational

and inflectional.

At the same times we've been developing a set of

diagnostics, or tests, for each category

Thus, taking the affix -ness AND -ly is a good

test for adjectivehood.

A very important kind of evidence for

categories is distributional evidence.

________ can be a pain in the neck

Anger/*angry/*angrily can be a pain in the neck

Heights/*off can be a pain in the neck

For a distributional argument for category X we need a context

in which only things of category X can occur.

For example, is this a good distributional

context context for argueing for adjectives?

John thought of something very ____.

No, adverbs go here too. For adjectives We need something more like:

John became very ____.

John became very neat/*neatness/*scrub/*off.

For adverbs how about:

John worded the letter ______.

John worded the letter carefully/*careful/*care.

For prepositions

John put the book ____ the table.

John put the book on/under/on top/*top the table.

Or

John put the book right ____ the table.

John put the book right on/under/on top/*top the table.

Phrases: Argueing for constituency

Thus far structural evidence for parts

of speech. Moving on to phrases.

Remember there are two kinds of information in representations

of structure (trees), phrasal information, what words

make meaningful units, and category information, what

the categories of phrases are. So we'll be looking for

evidence of both kinds, evidence that the things we

hypothesize to be phrases are actual linguistic units,

and evidence that they have the categories we say they have.

We're going to call phrases constituents, because we generally

consider them in a syntactic context, so they are

constituents of the sentences they occur in.

Morphological evidence. (parallels the word-level morphological argument).

The possessive affix: 's.

Observation 1: The possessive affix attaches at end of entire phrase, not

onto the head.

- The king of france's haircut

- * The king's of france haircut

This is in contrast to what we saw before, inflectional and

derivational morphemes attaching onto words. What seems to be going

on is that the affix has a particular structurally defined position it

goes on to. This so different from other affixes that people have

argued that this should be treated as a different kind of thing

altogether. Sometimes the English

possessive is called a clitic. Rather than attaching to particualr

kinds of words like other affixes, clitics

attach to phrases or have structurally

defined positions. There's a discussion of a Serbo-Croatian

clitic near the end of Chapter 1.

Observation 2: Possessive only attaches to NPs

* a very handsome's crown (Adj)

We have something that attaches to phrases of a specific category,

namely, NP, so we have morphological evidence for phrase-level

categories, just as we had morphological evidence for word-level

categories. At the same time time, we have evidence for

the phrase-boundary, because the possessive affix pays attention to

where the noun phrase ends.

Semantic evidence (parallels the word-level semantic argument)

Mary looked very hard (Adj and Adv reading).

Adj reading: Mary looked merciless.

Adv reading: Mary put a lot of effort into her looking.

This sentence is ambiguous. It has two readings.

Ambiguities are very important in syntactic argumentation.

Why?

Just as there different sources for acceptability so there are

different sources for ambiguity. An ambiguity

means has a sentence two or more ways of being

interpreted. But the rules of the language

are suppose to account for meanings. Where

does that difference comes from.

We assume that the rules can provide

meaning differences in two ways. Different words are

chosen. Or different structures:

Their flight from Egypt was remarkable.

We saw the Eiffel Tower flying to Paris.

These two examples represent different

kinds of ambiguity.

The first ambiguity hinges on the meaning of the

word flight. This

is a lexical ambiguity.

The second case is different.

No word changes meanings between

the two readings. It's a question

of what the relationships among the lexical meanings are.

This is a syntactic or structual

ambiguity. In one case flying to Paris

modifies we (we are doing the flying),

in the other (slightly silly) reading,

it modifies the Eiffel Tower (the Eiffel

tower is doing the flying). [The question

of how we would reprsent this difference in trees

is a complicated one we set aside for now).

Next we look at semantic evidence based

on a structural ambiguity.

The president could not ratify the treaty.

- not-possible reading: It is not possible for the

president to ratify the treaty.

Even if he wanted to, the president could not ratify

the treaty, because he doesn't have the authority to do so.

- possible-not reading: It is possible for the president

not to ratify the treaty.

If he really wanted to come out strong against

disarmament, the president could not ratify the treaty.

By not ratifying it, he would make his position clear.

The structures we will assume:

- not-possible reading: [The president] [could not] [ratify the treaty].

- possible-not reading: I[The president] [could] [not ratify the treaty].

VP = not ratify the treaty

Now assume an adverb goes before the VP constituent. Then these

two different structures would predict different adverb placements.

- [The president] [could not] simply [ratify the treaty].

- [The president] [could] simply [not ratify the treaty].

And this works. (1) has only the not-possible reading;

(2) has only the possible-not reading.

Form of argument:

- A structural distinction posited which accounts

for one phenomenon. (the ambiguity)

- The same structural difference is independently

motivated. That is, the account in (1) is

not ad hoc. Other phenomena are accounted for by the

same structural distinction.

Further independent evidence:

- What the president could not do is ratify the treaty.

- What the president could do is not ratify the treaty.

These syntactic variations on the first sentence are called

pseudo-clefts.

(1) has only the not-possible reading;

(2) has only the possible-not reading.

Contraction facts

- [The president] [couldn't] [ratify the treaty].

- * [The president] [could] [n't ratify the treaty].

Distributional Evidence for Phrases

Preposing:

- I can't stand your elder sister.

- Your elder sister, I can't stand.

Call this second sentence a case of pre-posing.

Lots of elements prepose:

NP: This kind of behavior, I simply will not tolerate.

VP: I went to the new James Bond film, and very exciting it was.

ADVP: Very shortly, he'll be leaving for Paris.

PP: Down the hill John ran, as fast as he could.

VP: Give in to blackmail I never will.

Some things do not.

- *Your elder, I can't stand sister.

- *Elder sister, I can't stand your.

- *Sister, I can't stand your elder.

- *Your, I can't stand elder sister.

Hypothesis: only a whole phrase (and not just PART of

a phrase)can be preposed.

Things which are not constituents do not prepose

Jean rang up her mother.

Jean stood up her date.

Jean looked up his phone number.

* Up her mother Jean rang.

* Up her date Jean stood.

* Up his phone number Jean looked.

Why do we say that strings like

up her mother in these sentences are

not constituents?

One: word order flexibility of up

Jean rang her mother up.

John ran up the hill.

*John ran the hill up.

Two: When the particle precedes

the NP, the particle and verb

must be adjacent, in contrast

to prepositions and verbs:

* Jean rang right up her mother.

John ran right up the hill.

Jean reluctantly rang up her mother.

*Jean rang reluctantly up her mother.

Jean ran reluctantly up the hill.

This suggests the verb and particle form a constituent

in these phrasal verbs. If the verb and particle form

a constituent, then the particle and NP do not.

Is the argument clear here?

[-PV ring up]-PV her mother

ring [-PP up her mother]-PP

*[-PV ring [-PP up]-PV her mother]-PP

The particle can't belong to BOTH constituents.

Preposing Constraint

Only phrasal constituents (i.e., whole phrases)

can undergo preposing.

Postposing

He explained to her all the terrible problems he had encountered.

* He explained all the to her terrible problems he had encountered.

Movement Constraint

Only phrasal constituents (i.e., whole phrases)

can undergo preposing or postposing (movement).

Next constraint:

Sentence fragments must be phrasal constituents:

Who was he talking to?

To his elder sister.

His elder sister.

*Elder sister.

* sister.

Who are you ringing up?

* Up my sister.

We started out looking for arguments for

phrasal constituents but really

Two notions emerging as important:

Constituents

Complete phrases ( a special sublass of constituents)

An argument for categoriality. The other kind

of information our trees is category. To motivate

syntactic category as part of our notion

of structure we need some linguistic phenomena

that are sensitive to

category.

Two kinds of adverbs:

- Sentence adverbs: certainly, fortunately,

necessarily, obviously...

Sentence adverbs attach to S

- VP adverbs: carefully, completely, quickly,

steadily

S positions: The team * can * rely on my support *.

VP positions: The team can * rely * on my support *.

Why is this not an S position?

The team can rely * on my support.

Why is this not a VP position?

The team * can rely on my support

Why are these positions both?

The team can * rely on my support *

Can you articulate a property that these

positions share that makes them ambiguous?

Extend this. Why not:

*Jean rang up her reluctantly mother.

*Jean rang reluctantly up her mother.

More arguments for constituency

- Coordination

Jean climbed down the firescape or down the ivy.

* Jean rang up her mother and up her sister.

- Shared constituent coordination (Right Node Raising)

John walked and Mary ran up the hill.

John walked up the hill and Mary ran up the hill.

* Mary rang and Jean picked up Mary's sister.

Coordination Constraint:

Coordination is possible only between contituents.

Shared Constituent Constraint:

Shared constituent coordination is possible

only when the shared phrase is a possible phrasal

constituent of both clauses.

Problems with Coordination. As we noted at the beginning

of the chapter, not all the diagnostics we come up

with are going to converge on the same result.

Here's a case in point:

The professor gave her favorite student a book on syntax and her nephew a surfboard.

What is being coordinated here? Do these strings

form a constituent? What do the other tests say?

? Her nephew a surfboard the professor gave.

In general coordination is a less reliable test.

Anaphora test

The man who wrote the book on Transformational

Grammar was greeted at Kennedy Airport today by massive

crowds, cheers, and fainting. He is universally adored.

He refers to the same individual as the entire Noun

Phrase:

The man who wrote the book on Transformational

Grammar

We call this the antecedent of the pronoun..

Pronoun takes entire NP as antecedent and syntactically behaves

like entire NP.

It's really a pro-NP not a pro-noun.

* The he who wrote the book on Transformational

Grammar was greeted at Kennedy Airport today by cheers

and fainting.

Pro-VP (so, as):

Mary will never agree to secession, as I've told you repeatedly.

It now appears that Mary might agree to secession, and

so might Jean.

Pro-Adjp(so):

Many consider John extremely rude, but I've never found him so.,

Pro PP (there):

Mary wants to go to Florence.

Gina already lives there,

But what about this?

Mary loves Florence,

but she lives there anyway.

Refined hypothesis: The pronominal form there has

the distribution of a PP, but it's antecedent

can be anything that denotes a place,

either a PP or an NP.

General pronominalization Claim:

An adequate description of pronominalization

needs to refer to both constituents and categories.

Ellipsis

See examples (100) and (101) in the text, pp. 82,83.

John won't put the vodka into the drink but his brother will.

Another process that takes all of a phrase, nbot part of it,

limited in this case to VPs. We have a diagnostic for

VPs.

Word versus phrases

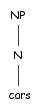

Sentences of the following kind:

We argue now that the italicized words are phrases

as well as being words. Cars is an NP.

Useful is an AdjP. So

there are single-word phrases.

The first idea is that all the processes that we claimed

applied to FULL phrases apply to these single-word

strings.

Preposing: Cars, most Londoners can't stand.

Pronominalization: Jane is rude, as is her sister.

Conjunction: Sara is intolerant and very rude.

Shared constituent coordination: John truly loves and Mary truly detests

computers.

VP ellipsis: John can't ski, but Mary can.

We noted that conjunction is a somewhat unreliable test.

But conjunction does seem to require parallelism.

That is, the things conjoined need to be alike.

Notice that in our a example a phrase is coordinated

with a single word intolerant. Examples illustrating

the need for like things in coordination:

John buys very new cars and very old paintings.

*John buys very new cars and very.

*John buys very new cars and old.

John buys cars and very old paintings.

The second idea is that wherever we have full phrases,

these one-word strings can occur too.

John is keen on very fast cars.

John is keen on cars.

Cars can be extremely useful.

Cars can be useful.

Thus these one-word strings have the same distribution

as phrases.

In other words, these one-word strings are passing the distributional

test for phrasehood.